A fish out of water. A bike without a chain. Out to sea. A stranger in a strange land. There are many metaphors for culture shock, all of which attempt to describe the unique experience of being far from one’s home country and culture. Culture shock is defined as the feeling of disorientation experienced by someone who is suddenly subjected to an unfamiliar culture, way of life, or set of attitudes. None of the metaphors or definitions quite capture how it feels to be in a new place for the first time. Culture shock can feel extremely alienating and lonely. And none of us are immune to its effects. Gaining a deeper understanding of this phenomenon and how it works can help us prepare for what lies ahead.

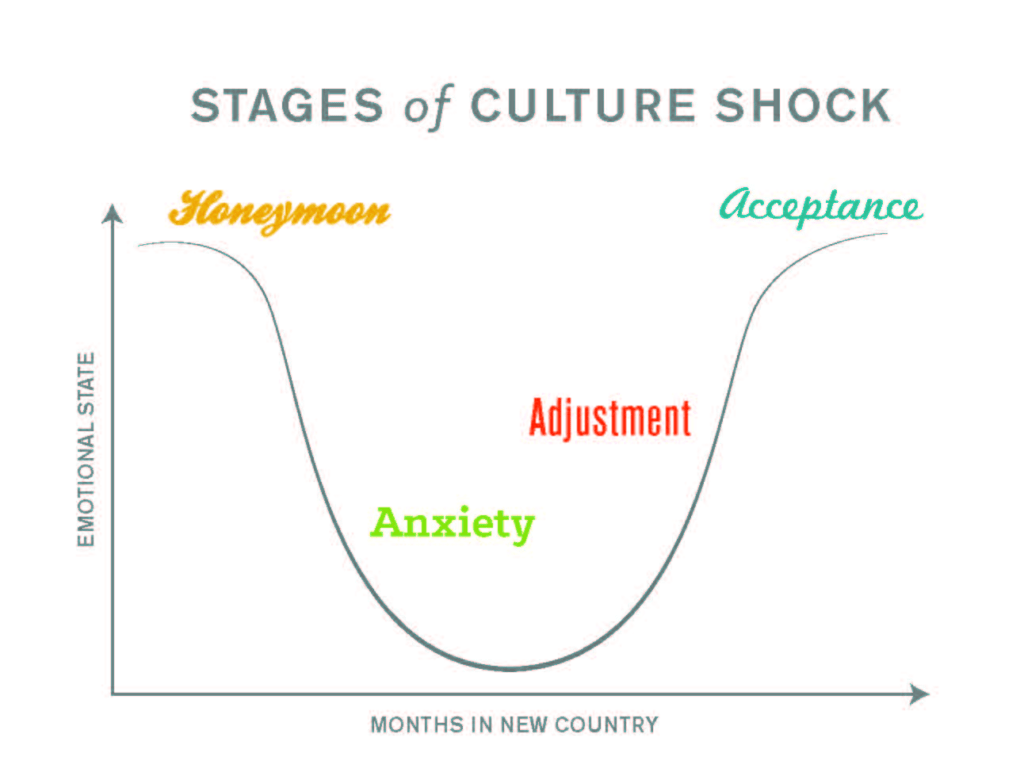

Scientists have studied culture shock for over a century. It is referred to as “acculturative stress” and rather than focusing on the purely negative aspects, psychologists describe it as a process of stress and adjustment. Most people are familiar with the traditional adjustment curve:

Oberg stated that although not all people experience these stages with the same intensity or at the same time, everyone experiences all of them at some point in their sojourn. The first stage is a state of euphoria, or the honeymoon phase, when we are filled with excitement about being

in another country and experiencing a new culture. Eventually, as the excitement dies down and day to day challenges arise, we enter a state of crisis and anxiety, causing us to have hostile feelings about the host culture. The longer we are immersed in the culture and learn more about it, we adjust and recover from those hostile feelings. Finally, after some time we adjust even more and fully accept the new culture.

Over the years, however, a variety of patterns have been observed by psychologists, including an inverse U-curve, in which anxiety is highest at the beginning and end of a person’s stay abroad, and a J-curve, in which social difficulty and depression are at their highest 24 hours after entry, drop steeply after 4 months and subsequently level off. Since so many different adjustment patterns have been observed, recently some psychologists have argued that there is no “one size fits all” when it comes to how we manage time abroad. They believe the “person-centered” approach to be a much more valuable way of studying adjustment over time. Instead of focusing on how different variables affect the individual, they prefer to study how different individuals relate to one another. After all, each of us is unique, and we react in different ways to our environment based on our personalities, expectations, previous experiences, etc. So what are the individual factors that can affect our time abroad? And is there anything we can do to impact how we as unique individuals adjust to being in a new country?

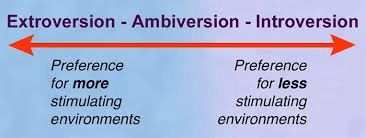

One of the factors that determines how we react to cultural stress is our personality. The most well-known and often misunderstood dimension of personality is extraversion. We tend to believe people are either introverts or extraverts. However, extraversion is a continuum that describes what gives us energy and how we prefer to recharge. No one is 100% extraverted or introverted, rather we tend to fall somewhere in between these two extremes. Not surprisingly, people who are closer to the extraversion end of the spectrum tend to have an easier time adjusting to new cultures. That is because being in a new country means meeting many new people and spending a lot of time around those people, and extraverts thrive in these situations. But all is not lost for introverts who go abroad. Being an introvert doesn’t mean not enjoying making friends and being with people. Introverts simply prefer to be alone after spending extensive time in groups. They only have so much energy to spend in social settings. There are many coping strategies that introverts can employ while studying abroad, the most important of which is to know what they need to recharge. Taking some “me” time after a long day with others is important for introverts to prevent overwhelm and remain upbeat and positive. And despite common misconceptions, sometimes extraverts need alone time and introverts need to be around others.

Historically, intelligence was known as a general ability, however in recent decades it has come to light that there are many types of intelligence. The “alternate” intelligence we hear about most frequently is emotional intelligence. But have you heard of cultural intelligence? Cultural intelligence, or CQ, is defined as the capability of an individual to function effectively in situations characterized by cultural diversity. CQ has to do with our interest in interacting with people from culturally diverse backgrounds, our knowledge about other cultures, our ability to adapt to new cultural norms based on our environment and our ability to adjust our verbal and non-verbal actions to suit the context in which we find ourselves. It is argued that CQ can help us adapt to culture shock. The higher our CQ, the lesser the effect of culture shock on our ability to cope in new situations. In addition, regardless of what our CQ is now, we can increase it through training and exposure to new cultures. Often, our first introduction to our host culture is upon arrival and at in-country orientation. This is where we first learn about the cultural norms of our new home. But starting to learn about the new culture earlier can arm us with the information needed to develop a broader cultural mindset. Try meeting and talking with people in your community from your host country. Read novels by authors from your destination. Read about its history. Find social media groups centered around the culture. In the U.S., we tend to live and socialize in very segregated pockets of people who look and talk and think like us. Seeking out opportunities to have genuine interactions with all types of people before going abroad is a solid first step toward combating culture shock and broadening our horizons.

What other ways can we cope in an entirely new place? Many of the most effective coping strategies are interpersonal. A recent study found that relating to others with empathy and perspective taking is significantly associated with lower stress levels abroad. The more empathic we are and the more we are able to take on other people’s points of view, the more positive our interpersonal relationships and thus our adaptation to the stress of culture shock. In fact, our relationships are one of the biggest factors in how well we adapt in new environments. Students who spend time abroad generally have a tenfold increase in their number of relationships. A new local support network develops. The close knit community of students from our home country who are also studying abroad is a source of new friends that can relate to us in ways that others cannot. We can also rely on mentors like program leaders or others who are there to help us through the transition. Making local friends can also be important for cultural adjustment. Living with host families and attending local schools provide the benefits of day to day contact with host nationals – a crucial “insider” element to help us understand the new place in which we find ourselves.

One important finding of psychological studies around culture shock is the positive effect of tackling our discomfort head on as opposed to avoiding it. The problem-solving approach involves acknowledging how we feel, whether it be sad, angry, tired, lonely, confused, hungry or sick, and employing the same effective strategies we normally employ when we have those feelings. Sticking to our routines (such as exercising or listening to music when we’re stressed and hanging out with friends when we’re lonely) can be helpful in difficult times. Having a sense of humor can also help in adjusting to new situations. When I studied abroad in Spain for the first time, my American friends and I would speak “Spanglish” to each other using the Spanish words we found interesting (and very different from English). We essentially created our own language and had fun laughing at how silly it sounded. Sometimes we just have to laugh at our awkwardness in the new place and not take ourselves too seriously. This is a way of thinking meta-cognitively – of seeing ourselves from outside of ourselves. This perspective also allows us to realize that our time abroad goes quickly, and before we know it, it’s over. All of the little and seemingly big things that annoyed or frustrated us while we were travelling become miniscule in the bigger picture, and our overall experience abroad comes to light.

Is going abroad worth the sometimes painful and lonely periods we must endure? Why bother dealing with culture shock? Study abroad is a significant life event for the personality development of young adults. The leaving home process happens to most college age people, but leaving home and spending weeks or months in another country far from home takes that process to a whole new level. Nothing expedites maturity quite like this experience. It has been shown that spending significant time in another culture accentuates openness and agreeableness and increases emotional stability. Self-efficacy goes through the roof. After going through and learning so much, we feel like there is nothing that we can’t accomplish. So I ask you, is it worth it?